AIDS and Hunger - Malawi

AIDS and Hunger - Malawi

Story & photographs by Andy Rain

Picture this. You have a large family but very little money, so you work your farm, day in day out. But your crops dry up and wither because it has failed to rain. There is no food, nothing. The hunger that your children feel turns from a child’s screams into ‘ edema’, swelling of the stomach. They fall sick and you want to rush them to the clinic. But the clinic is 30 km’s away and you don’t have the strength to carry them such a distance. So you search for whatever food you can, banana roots or maize husks, normally chicken feed. No help comes, just another day of scorching sun and endless worry. Your kids’ ‘edema’ is now ‘marasmus’, emaciated and matchstick like they don’t have the strength to scream anymore. Their silence soon becomes death.

This tragic scenario might become reality for millions of people across the southern African region this winter. Malawi’s food crisis is acute to say the least. Aid agencies have estimated that up to 14 million people across the region in Malawi, Zambia, Zimbabwe, Mozambique, Swaziland, Lesotho and Angola may face starvation if food is not brought in.

Little more than a decade ago the Malawi currency (Kwacha) was one to one with the US dollar. Now it is 80-1. Poverty is threatening to ravage this beautiful country and HIV/Aids is making matters a lot worse. More than half the population are children and the average life expectancy is just 39 years. Half a million people have died from Aids and there are a million Aids orphans. The gap between rich and poor has become so vast that two worlds exist in one country.

Floods which swept away newly planted maize just over a year ago, followed by drought leaving the spring harvest a fraction of its size have largely caused the food crisis. UNICEF (the United Nations Children’s Fund) believes that 3 million people are at risk.

“There is an appeal going out”, says Carrol Bellamy, Executive Director of Unicef, “but there has not been adequate funding. We need to support 6 nations severely affected, Malawi being among the worst. People are dying and many more will likely die this spring”, she explains. “Moreover HIV is an obstacle of enormous consequences”, says Belamy. “If HIV were to stop tomorrow we would still have an increase in Aids orphans for another decade”.

Many locals in villages echo her words across the country. In the village of 'Searching for the world’, 40 km’s north west of Lilongwe, the capital, I find a small community of 25 families. When I arrive there is little sign of life. Men and women sit apathetic in the shade with nothing to do. The kids enjoy me though, but they are thin, so stunted its hard to imagine that these are young men. There skin is dry and peeling. None wear shoes. “ We don’t know what we’ll do”, says Gama Bazare, 48, headman of the village.

“We don’t know if we’ll be alive for the next harvest. Six people have died of hunger in the last few months. In Kalowa village, 30 km’s east of Lilongwe the picture is much the same. Women sit in the shade holding their emaciated children. Their bellies are bloated, their legs matchstick like. “ We buried 3 in one grave last month”, explains Jon Liwonde, 34. “ We were too tired to dig them each a grave”.

In the heart of southern Malawi the village of Sapanga sits in a dry valley below the Sese and Sakala Mountains. Just 25 km’s away from Lilongwe, it is in all reality, a world away. Fields of maize stalks stand withered and lifeless, testimony to the merciless elements of nature.

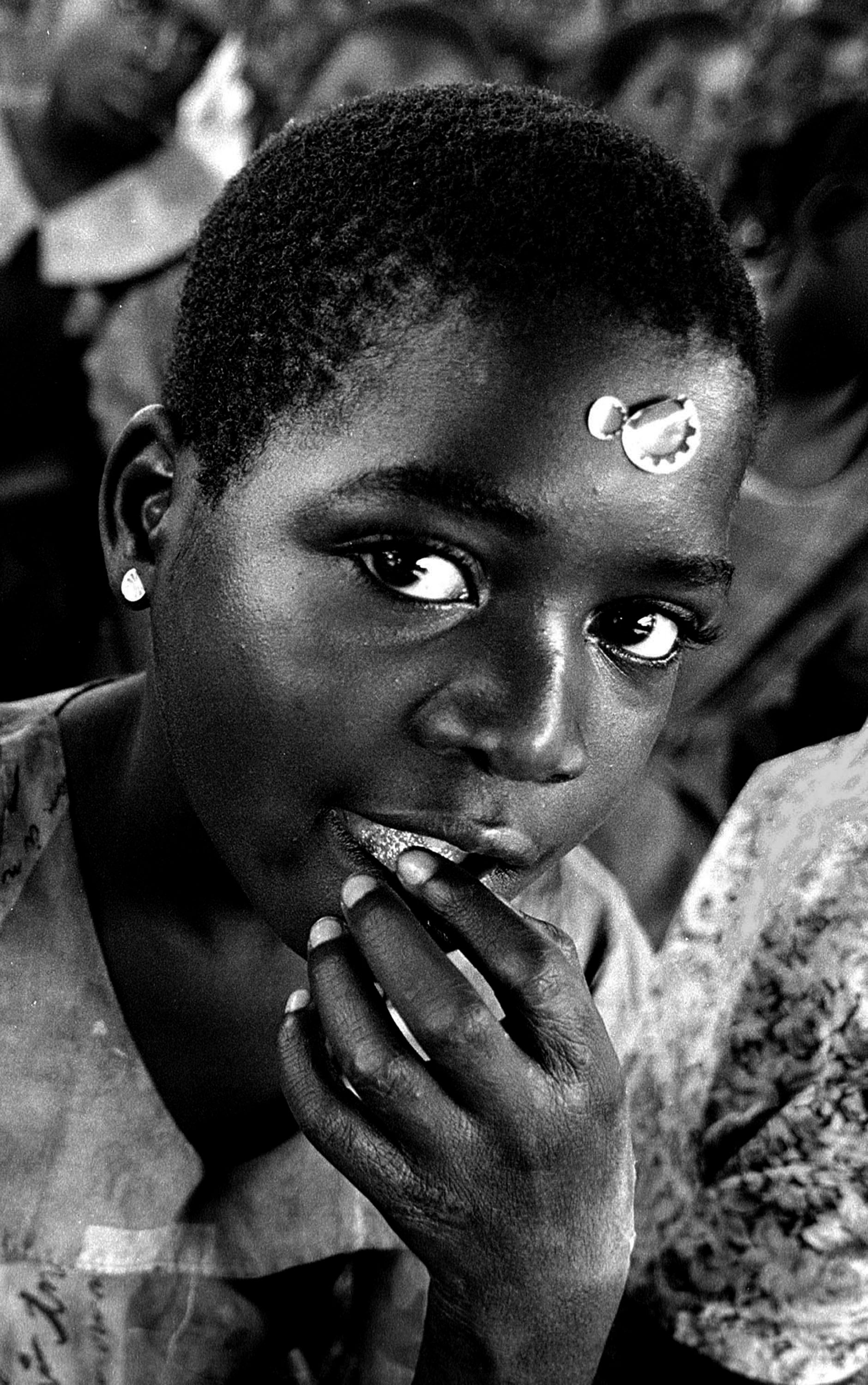

I pass women carrying buckets of water on their heads and a man and boy pushing a bicycle piled high with wicker chairs up a steep dusty climb. The sun is scorching hot, the land dry. The closest main road is 15km’s away. In Sapanga, a village of some 10 mud huts, I am greeted by a handful of women. Beside them are 93 young Aids orphans learning English under a tree. There are no men in the village. “They’ve gone off to find money”, says Rosmary Kulemera, 32. “Sometimes my husband will bring back flour or something, but sometimes he drinks it all”. Communities usually help one another but in these hard times things have changed.

“Our future is looking grim”, Fainess Tawakabi, 65, the head woman tells me,“We don’ t know what we’ll do next”. As I leave them in a 4-wheel drive air-conditioned Unicef Toyota the children clap their hands and sing a farewell song. In life there is always irony. I find some in the Limbe Transit Depot where more than 5,000 tons of new maize has arrived from local suppliers. A further 13,000 tons of old stock from South Africa is piled high as far as the eye can see. I shake my head and drive south from Balntyre, the nations commercial capital, towards the Mozambique border, passing kilometer after kilometer of wonderfully green tea plantation. The land reflects continental Europe. All this land for tea? While hundreds of thousands of people are starving in the rural lowlands?

” But we need the tea for our economy”, explains my EU guide. The land is owned by Europeans, mainly British. During the drive back towards Blantyre, heavy rain clouds sail in from the south; I can’t help but feel that there is something drastically wrong with the way the world works.

The ways of the world are thrown at me once again in Blantyre at the Shoprite Supermarket. Anything and everything is available. The fruit and vegetable racks are full. So too is the frozen food section. Lite & crispy lemon cheese 6 packs, Steak Sizzlers, sausages, hams, and all kinds of cheese, meats and salads. Juices, soft drinks, beers, wines and an endless array of chocolates. In the newspaper rack, the local daily has a large picture of a crying malnourished child on its front page. The headline reads, “The Face of Hunger”.

In Malawi and across southern Africa today poverty is eating away at the very fabric of society and it is the children who are paying the heaviest price. Robbed of an education, many are forced into violent crime as a means to survive. Countless others are becoming Aids orphans with little chance of a bright future. The lack of political will to free people from poverty is keeping them there. The Japanese government has pledged US$ 30 million in food aid to the starving across southern Africa. The aid is part of a ‘ Koizumi Initiative’ on sustainable development aimed at supporting education and preventing infectious and parasitic diseases.

The international community and UN aid organizations can help to alleviate poverty, the needs of the poor and hungry, but nothing will change just by throwing in large donations to aid organizations. This might prevent a few hundred thousand people from starving to death, but it won’t tackle the long-term needs of southern Africans. Without a long-term approach to solutions of poverty, HIV and sustainable living, both by the international community and local governments, proposals put forward on such issues will remain just words in countless documents; on tables of endless meetings, between delegates who harbor little understanding of the needs of 80% of the world’s population.

It is an image and the gentle words of children from the village of Sapanga that I carry with me from Malawi. “Travel well our visitors”, the orphans recite from a traditional song. “ May God look after you”, they sing. Someone must do the same for them.

end